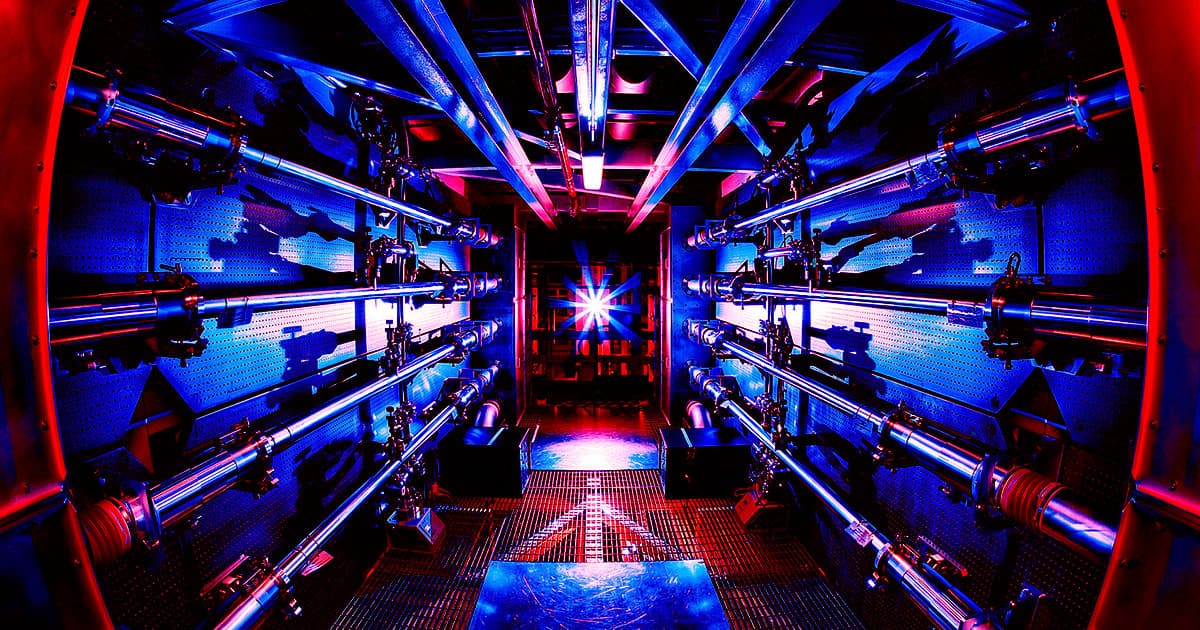

Last year, researchers at the National Ignition Facility (NIF) in California announced they had achieved a major breakthrough: they produced fusion energy by heating up a peppercorn-sized sample of two hydrogen isotopes well past the temperature of the Sun's core using a massive laser, a process known as inertial fusion.

At the time, scientists called it "a huge advance for fusion and for the entire fusion community" and "the most significant advance in inertial fusion since its beginning in 1972."

"To me, this is a Wright Brothers moment," Omar Hurricane, chief scientist of the NIF's inertial fusion program, told CNBC at the time.

Just under a year later, and a sobering reality has set in: follow-up experiments attempting to recreate the landmark achievement are falling far short of expectations, Nature reports, forcing the researchers involved to take a step back and reevaluate the entire thing.

In fact, according to that reporting, their best results since have only managed to get to 50 percent of the energy that last year's landmark experiment produced.

It's an unfortunate setback that goes to show just how far we are from creating a perfectly sustainable and green source of energy by fusing atoms together. And that's despite a series of purported breakthroughs and billions of dollars in funding — the laser device at the NIF itself, for instance, cost an eyewatering $3.5 billion to develop and build.

"The fact that we have done it is kind of existence proof that we can do it," Hurricane told Nature. "Our issue is doing it repeatedly and reliably."

Last year's experiment yielded 1.3 megajoules of energy after 192 laser beams shot 1.9 megajoules of energy at a small pellet of hydrogen isotopes. While that means they only got back roughly two thirds of the energy they put in, the experiment crushed the previous record 1,000-fold.

Other more conventional attempts to turn fusion energy into reality involve heating plasma to millions of degrees inside massive donut-shaped reactors.

Hurricane and his colleagues are now desperately looking for why they aren't able to recreate these numbers. Back in October, trials only yielded anywhere between 400 and 700 kilojoules of energy, according to Nature.

In other words, the technology is still in its infancy and is extremely difficult to predict.

And that doesn't bode well for the future of the NIF's inertial fusion program.

"I think they should call it a success and stop," Stephen Bodner, a physicist, who headed a similar program at the US Naval Research Lab, told Nature.

READ MORE: Exclusive: Laser-fusion facility heads back to the drawing board [Nature]

More on fusion energy: Startup Says It's Honing in on Simple Solution for Practical Fusion Power

Share This Article